Blogging from China has been challenging. We’ve been very busy, and dealing with the Internet there is often frustrating and eats up time. I’m writing now from Nepal, which has a less restrictive government, though we are definitely in the Third World.

Leaving Beijing

The morning of Wednesday, November 9, is very smoggy. The clear weather we had enjoyed has passed.

We arrive in Guilin around 6pm, and are met by John, a very chatty driver. The sister city of Guilin is Orlando, which sends teachers over here. John is one of their eager students. It’s raining here, light and steady; John says tomorrow will be sunny.

The Golden Oriole is a very nice modern hotel, with a premium location. The signal landmark of Guilin is a rock formation called the Elephant. We can see it outside our room. The hotel — indeed the town — is full of elephant imagery, though there aren’t any of the animals to be seen. Reminds of home, with all the fiberglass bears on every corner!

There’s the trunk on the left, sipping water. The foliage is the hair on its head and back.

Karsts

Thursday, November 10. The name for the type of rock formation that made the Elephant is “karst.” And the area surrounding Guilin is famous for these limestone formations. Some are small, like a house, some as big as an office building, and some are like small mountains.

There is no better place to view these amazing hills than along the Li River. So, early on the morning of the 10th we pile into John’s van and set off to take a cruise (It’s not really John’s. He has a driver with a van. I just wanted to keep this short. But now that I’ve screwed that up, back to our story.) Along with about 3,000 other tourists. There’s a fleet of river boats waiting for us at the dock, and lucky for us, Audley had arranged the best seats on one of the better boats. There we meet another couple who was using Audley to travel from England to China.

The weather has cleared, though it hasn’t warmed up like John’s weather report promised (we later find out that his weather channel is dismally optimistic in this regard). But as a result, our view of the scenery, floating down the river, is perfect. And this scenery is just awe-inspiring. It is famous throughout China for its beauty, and justifiably so. It appears not only in countless Chinese landscape paintings (the reason I chose to come here instead of, say Xi’ An) but on the back of their 20RMB bill!

It will take me a while to develop a painting that does it justice, so here are a couple of the 800 photos from that excursion:

The cruise ends in Yangshuo, the town most famous for these rock formations. The people here have been among the poorest in China, because the karsts have left them with very little room to grow things. Now, of course, tourism is eclipsing farming here, but the area is slow to catch up — partly, John tells us, because of certain government regulations that prevent change.

Yangshuo

Beijing is very cosmopolitan. Guilin seems to me quite modern, in its way. Yangshuo is a throwback. Anthony Bourdain would love it here. The first thing we do, after getting off the boat and making our way down a half-mile of souvenir shops, then winding through another length of small shops, is go see about a cooking lesson. In the process, Mary observes that most of the stuff they’re selling in these shops is cheaper either on Canal Street back in NYC, or on line!

Well, the restaurant in town offers a cooking lesson that Mary could easily give herself. And it’s not the one in our itinerary. Enough said that Mary puts the matter straight, and we are scheduled for a class — just the two of us — at the Yangshuo Cooking School. But more on that later.

We’re driven about 18km out of town to the Banyan Tree Yangshuo hotel. “Hotel” doesn’t quite do it justice, as it must take up at least 10 acres of land along the Li River. It is simply the most beautiful hotel I’ve ever stayed at. Our room (suite, really) is in one of a group of small buildings surrounding a landscaped garden with a pond that has a beautiful tea house sitting in the middle of it.

Here’s Mary’s photo of it:

We settle in, but not for the night.

Impression

At 6:30 John takes us back into town to see Impression, a spectacle that was designed by the creators of the shows that we’ve all seen at the Beijing Olympics, and actually forms the basis of some of those shows. There are lines of buses parked along the way to the entrance. They have brought about 3,500 to see the show. We sit in an amphitheater facing the river, with a line of karsts as a backdrop.

The show itself doesn’t disappoint. It’s an hour-long light-and-sound spectacle with a cast of more than 600 locals — all amateurs. It depicts a year in the life of a village through the four seasons: children sing and play; adolescent boys and girls play out the “dancing day” festival; a couple of women sing songs in what Mary describes as “the key of scorched cat minor;” fishermen guide a fleet of bamboo rafts across the water in front of us, with a couple of representative cormorants. One of the first songs the men sing is about how they are farmers and fishermen by day, but come here at night to perform. Remember, this is a Thursday night, so they have to get up again early, and all those kids have to finish their homework. They put on this show every night, except for the coldest months of the year, and during the high season, twice! And on the national day, up to four times!

The effect is what it must have been like sitting in the bleachers at the Olympic Stadium, only part of that was actually as simulation of what we actually saw!

Beer Fish and Yangshuo-style Eggplant

On Friday morning, the 11th, we meet John for a trip back to Yangshuo. There we meet Sophie, our teacher, who was a student of an Australian woman who settled in a small village on the outskirts of Yangshuo to start a cooking school. Our first stop is the market, and a review of vegetables and herbs, and an introduction to a few new ones, like Chinese lettuce. We then walk next door to see the meat market, which has tables selling different cuts of meat, but also stalls that served as abattoirs for smaller animals. ‘Nuf said. We then pile into John’s van. The teacher would make her way to the school on her motor scooter.

The village is quite tiny, about a half hour out of town, and very rustic. I mean most Westerners I know would run screaming the other way kind of rustic. Let them take the three-course lesson at Cloud 9 Restaurant and learn how to cook like the corner takeout. “If you can’t run with the big dogs, stay on the porch,” I always say.

We start by adding some minced garlic and scallions, salt and a touch of oyster sauce to some minced pork, then adding the mixture to some daikon sliced like a book, a mushroom, and a cube of fried tofu (Make a lid out of one side of the cube, push the meat in.) We use the rest to make a meatball, and put our creations into a numbered bamboo steaming basket (mine is #19).

Next is Eggplant, Yangshuo Style: Slice some Asian eggplant — the skinny purple kind — and stir-fry on medium heat, squeezing the slices with the spatula once they’re a little brown. Add garlic, julienned ginger, a dab of black bean and chili paste, and oyster sauce. Voila! or the Chinese equivalent. That’s our appetizer for what’s going to be our lunch today. Mary’s turns out better than mine.

Then Pijiu Yu, “Beer Fish.” This is a firm white fish that is browned in the wok (we told them about our experience with carp, so we used catfish for this), then surrounded by sliced tomato, carrots and diced stem of Chinese lettuce. Once it has some color, it’s pushed to the side and the vegetables are stir-fried. Then half a cup of beer is added to the dish, and it is covered, until the fish is fully cooked.

Next came Chicken with Cashew nuts, but not like the one you get from the local Golden China takeout. Finally, stir-fried Chinese lettuce: the greens from that lettuce, stir-fried with garlic and a little salt or oyster sauce. Mary wins again.

After having the lunch we have just made, we’re driven back to the hotel for an afternoon and evening relaxing. Having this much fun turns out to be more strenuous than I thought.

Because of the kerfuffle (Holy cow! My spelling checker recognizes “kerfuffle”!) at The Wall, we are treated to a dinner at the hotel, guests of the Beijing tour agency. This is unexpected and grand. Prices there are expensive! We order modestly — cashew chicken, and yellow fungus with asparagus. John gleefully insists we also have a spicy dish of beef tenderloin. I don’t know if he has vicarious pleasure in doing this or Schadenfreude. (“Schadenfreude,” too! Sophisticated spelling checker!) The cashew chicken? Mary wins again!

On the Road Again

It’s Saturday, November 12. We’re up early, and take a walk around the grounds of the hotel. There is light rain falling, and the hilltops in Yangshuo are wrapped in mist, “Like a silk scarf around a pretty girl’s neck,” John says. Who knew this geeky guy was such a romantic!

After breakfast we’re driven back to the Guilin airport, and board a plane bound for Kunming. Kunming is the only city with a flight to Kathmandu, short of flying to Delhi or even Bangkok! We’re here just overnight, there is no good connection between the flights Guilin/Kunming, Kunming/Kathmandu. I suspect the Kunmingers (Kunmingians?) have something to do with that, because I don’t think any tourist would intentionally go to Kunming. The residents call it the Spring City, or City of Flowers. I’d call it Jersey City East, but that would be unkind to Jersey City.

We’re driven to a grand old hotel of the old style, the Zhong Wei Kunming Green Lake Hotel. This is an old building, beautifully restored. I’m guessing it’s pre-Mao, since it is located across the street from Green Lake Park, which has been a Chinese tourist destination for ages. And when you say “ages” about something Chinese, you’re talking serious time-spans, brother.

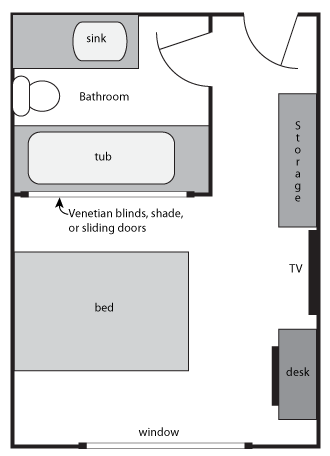

As an aside, I’d like to post an observation about the layout of hotel rooms in China. In three of the hotels there, we saw a curious pattern. As you enter the room, there is storage on one side and a door to the bathroom on the other. On one side of the bathroom there is a luxurious bathtub. OK, nice, but not unusual. On the same side as the storage, there’s a large TV screen, usually Samsung, never LG! But that’s not the point. Opposite the TV is the bed, so you can watch TV while in bed. What is unusual, is there has been either a venetian blind, an electrically operated, two-meter wide shade, or a set of sliding doors between the wall of the bathroom and the rest of the space! Nice if you want to watch TV while soaking in the tub, I guess!

In the morning, after another breakfast where we can choose between Chinese or Western items on the buffet (This time they had frosted Dunkin’ Donuts style doughnuts!) we take a walk in the park. The driver won’t be coming for us until about 11:30. Green Lake Park has something for everybody: seagulls to feed, trinkets and toys to buy, junk food, rides, boats; tai chi and other sessions for older folks; old guys singing ballads; a serious badminton court; beautiful scenery and buildings; bonsai! Really impressive ones!

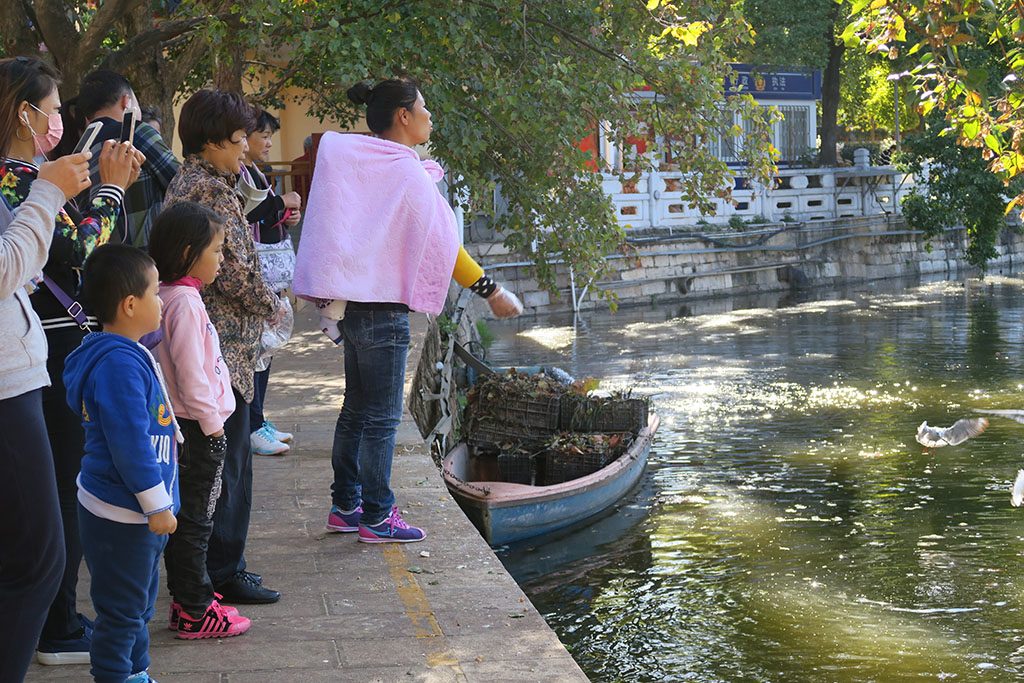

After a while there, Mary returns to the room. I walk around the park looking for subjects to draw. The main station for feeding the seagulls is right by our entrance the to park. A young woman with a baby sleeping in a carrier on her back sells birdseed. Every once in a while she walks from her stand to the side of the lake and calls out “Wee-U!” and the gulls congregate. And so do customers. This is a great subject for a painting, but it’s too crowded, and people come and go too quickly, so I take some photos and move on.

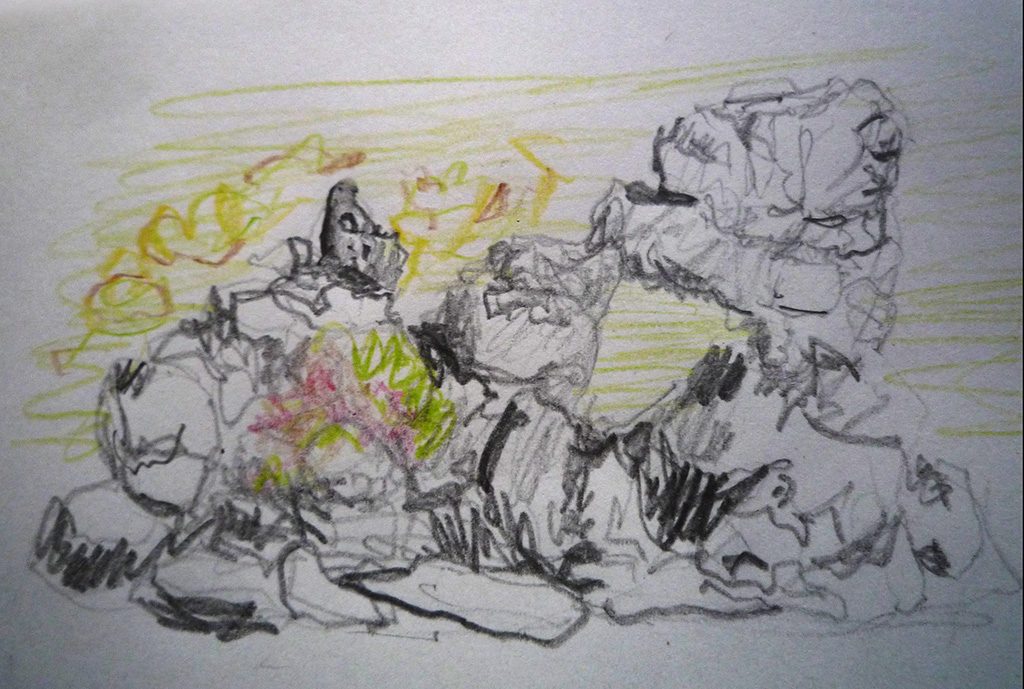

A little ways down there are two stands of the fabulous, gnarly, pitted rocks that the Chinese are so fond of. These were a lot of fun to draw:

At 11:30 the driver arrives.

Next: GOIN’ TO KATMANDU!